China’s Chang’e-5 lunar rock samples reveal Moon’s recent volanic activity

China’s lunar exploration program, also known as the Chang’e Project (named for the Chinese moon goddess Chang’e), began in 2007 with a lunar orbiter dubbed Chang’e-1. Subsequent missions landed on the lunar surface and Chang’e-5, launched November of 2020, successfully returned lunar rock samples to Earth.

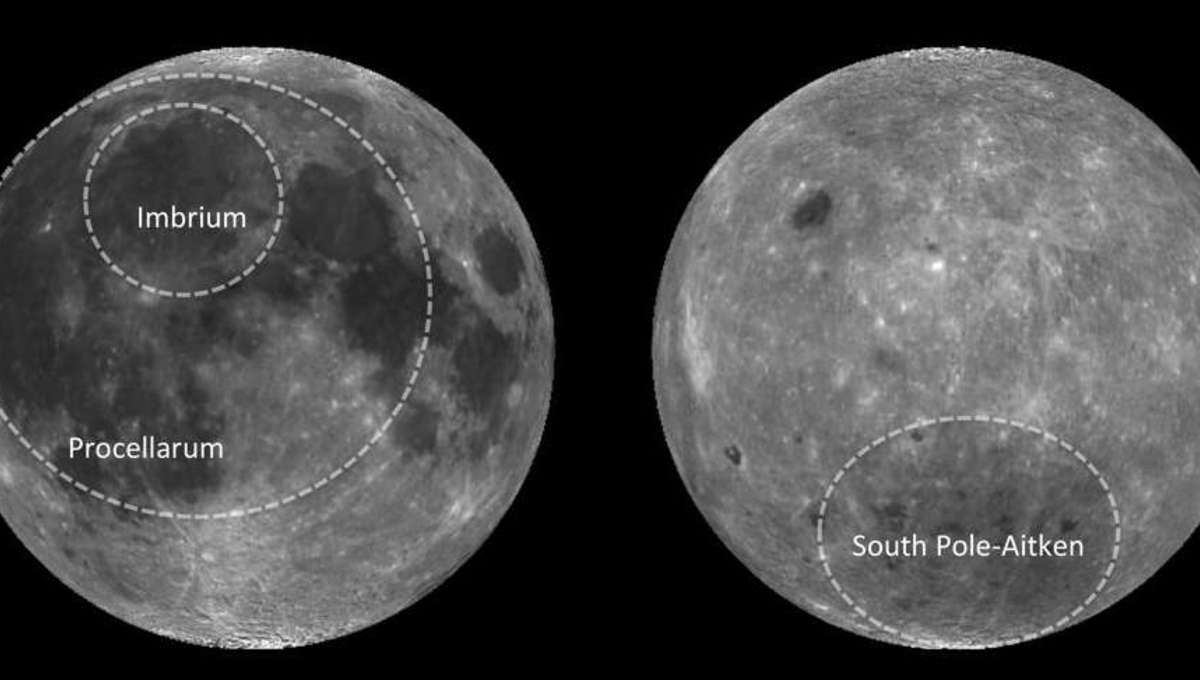

Chang’e-5 touched down at Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) on December 1, collected 61 ounces of lunar basalts, and returned to Earth a little more than two weeks later. All told, round-trip travel time was just less than 23 days. Pretty impressive for a trip of roughly half a million miles. Having returned the Earth, the samples were studied to determine their composition and age. The results were published in the journal Science.

More Moon

The landing site was chosen specifically because orbital observations indicated relatively young geology. Estimating the geologic age of lunar regions, and other celestial bodies, is complex and involves more than a little guesswork. Examination of the samples returned by Chang’e-5 helps to constrain some of those variables and give us a clearer image of the Moon’s evolution.

Determining the age of geologic activity on the Moon and elsewhere relies primarily on the distribution of impact craters. On Earth, there are relatively few impact craters for a couple of reasons. First, Earth’s atmosphere prevents the majority of impactors from reaching the surface. Second, Earth remains geologically active, so very old impact sites get recycled through erosion and tectonic activity. On bodies like the Moon, however, impact sites tend to remain, making them a good measurement of age. The thinking goes: the fewer impact craters present in a given region, the more recently it was geologically active.

Regarding the Moon, we have the benefit of returned samples, primarily from the Apollo missions, to further constrain the age of specific regions via radiometric dating. A clearer understanding of the age of various regions, compared to their distribution of impact craters, gives us a better model for understanding the ages of other locales in the solar system.

Those samples from the Apollo missions dated active volcanic activity on the Moon to about 3 billion years ago, and estimates for Oceanus Procellarum ranged anywhere from 1.2 to 3.2 billion years, meaning our models for geologic age had a pretty significant margin of error.

Analysis of the samples from Chang’e-5 validated the team’s suspicion that the regions was geologically younger than other, more cratered, regions of the Moon. An international team of researchers, including Alexander Nemchin from the Beijing Sensitive High Resolution Ion Micro Probe Center, worked on the analysis to determine their precise age.

“We used techniques developed for other terrestrial and extraterrestrial samples. It involves ion probes, instruments designed to analyze isotopes in small 10 to 20-micron spots on the surface of a sample,” Nemchin tells SYFY WIRE. “Importantly, it provides a confirmation that the Moon was active for much longer than previously thought. The Moon is a small body, and our general expectation is that any internal activity should disappear very quickly. The new data suggests that this may not be the case. Now we need to find what exactly is responsible for this apparent extended activity.”

The measured age of the samples ranges between 1.96 and 2.01 billion years ago. It’s possible, given their size — only 3 to 4 millimeters — that they may not be representative of the region as a whole. If they are, these findings push the date for volcanic activity a billion years later than previously measured. One possible explanation for extended magma flows relates to high concentrations of potassium, thorium, and uranium present in the rock. The radioactive nature of these elements could provide an additional heat source, contributing to extended thermal activity. Though there may be other contributing factors including tidal forces, which were stronger when the Moon was younger and closer to the Earth.

There’s still a lot to learn about the history of the Moon and other celestial bodies, and each new sample provides an additional piece to the puzzle. Chang’e-6, originally planned as a backup mission for Chang’e-5, is also a sample return mission slated to launch in 2024 and will provide additional samples which could clear up some of the remaining questions.

It’s nice to know that even our closest celestial neighbor still has so much to teach us.